By Jong-In Kim1, 2, Myeong Soo Lee1,3, Dong-Hyo Lee14, Kate Boddy3 and Edzard Ernst3

1Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, Daejeon 305-811, Republic of Korea

2College of Oriental Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

3Complementary Medicine, Peninsula Medical School, Universities of Exeter & Plymouth, Exeter, UK

4College of Oriental Medicine,Wonkwang University, Hospital, Sanbon, Republic of Korea

Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Volume 2011, Article ID 467014, 7 pages

3. Results

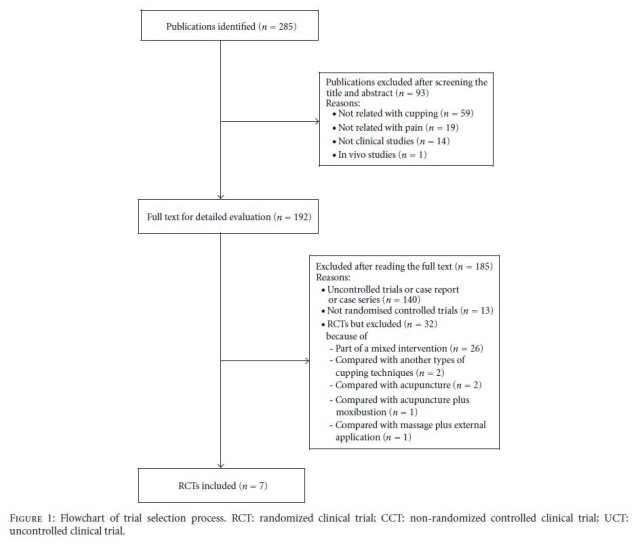

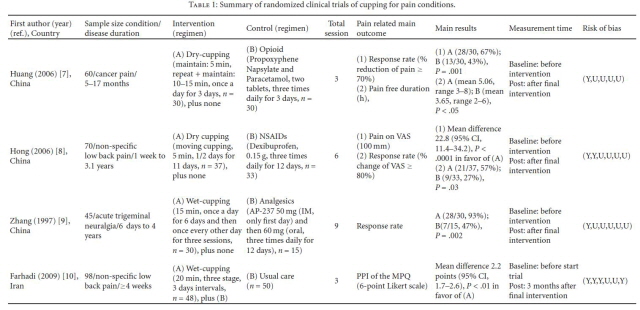

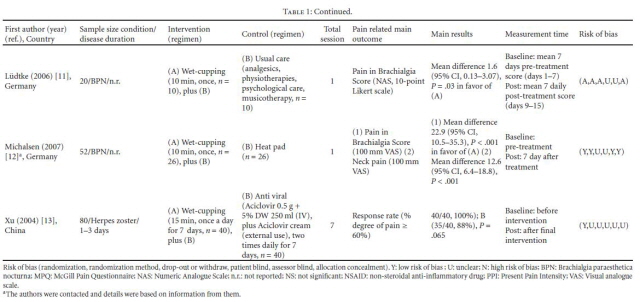

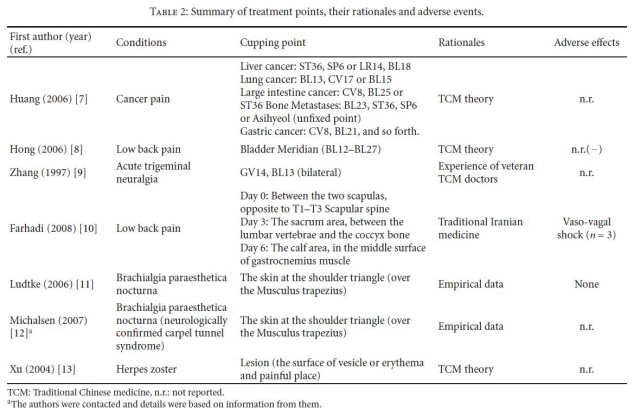

- 3.1. Study Description. The literature searches revealed 285 articles, of which 278 studies had to be excluded (Figure 1). One hundred and eighty five articles were excluded after retrieving full text and their reasons. Seven RCTs met our inclusion criteria and their key data are listed in Tables 1 and 2 [7–13]. One of the included RCTs originated from Iran [10], four RCTs from China [7–9, 13] and two RCTs from Germany [11, 12]. All of the included trials adopted a twoarmed parallel group design. The treated conditions were low back pain [8, 10] cancer pain [7], trigeminal neuralgia [9], Brachialgia paraesthetica nocturna (BPN) [11, 12] and herpes zoster [13]. The subjective outcome measures were theMcGill Pain Questionnaire [10], 100mm visual analogue scales [8, 10, 12], response rate [7–9, 13] and Likert scales [11]. Five trials employed wet cupping [9–13] and two with dry cupping [7, 8]. The number of treatment sessions ranged from one to about nine, with a duration of 5–20min per

session. The rationale for the selection of cupping points was stated in three RCTs to be according to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) theory [7, 8], clinical experience of expert [9], empirical date [11, 12] or to classical TCMtextbook [13].

One RCT followed traditional Iranian Medicine [10]. We contacted the authors for further information about an RCT identified in our searches which was published as proceeding paper [12].

- 3.2. Study Quality. Four RCTs employed the methods of randomization [7, 8, 10, 11] but none adopted both assessor and subject blinding. Assessor blinding was judged to have been achieved in one [12] of the RCTs and three used allocation concealment [10–12]. Sufficient details of dropouts and withdrawals were described in two RCTs [10, 11].

- 3.3. Outcomes. One RCT [7] compared the effects of dry cupping on cancer pain with conventional drug therapy and reported favorable effects for cupping after 3-day intervention (RR, 67% versus 43%, P < .05). Another RCT [8] compared dry cupping with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in nonspecific low back pain and suggested a significant difference in pain relief on VAS after treatment duration (MD, 22.8 of 100mmVAS; 95% CI, 11.4–34.2, P < .001). The third RCT [9] suggested that wet cupping reduced pain compared with analgesics in acute trigeminal neuralgia after the intervention period (RR, 93%versus 47%, P < .01). The fourth RCT [10] tested wet cupping plus usual care for pain reduction compared with usual care in nonspecific low back pain and suggested significant differences in pain relief (McGill Pain Questionnaire) at 3 months after three treatment sessions (MD, 2.2 of 6 points present pain intensity; 95% CI, 1.7–2.6, P < .01). The fifth RCT [11] reported that one session of wet cupping plus usual care significantly reduced pain during a week compared with usual care alone in patients with BPN (MD, 1.6 of 10 points score, 95% CI, 0.13–3.07, P = .03). The sixth RCT [12] showed favorable effects of one session of wet cupping on pain reduction compared with a heat pad in patients with BPN at 7 days after treatment (MD, 22.9, 100mm VAS; 95% CI, 10.5–35.3, P < .001). A further RCT [13] of wet cupping plus conventional drugs on pain reduction compared with conventional drugs alone in patients with herpes zoster failed to show favorable effects of wet cupping after interventions (RR, 100% versus 88%, P = .065).

4. Discussion

Few rigorous trials have tested the effects of cupping on pain. The evidence from all RCTs of cupping seems positive. The data suggest effectiveness of cupping compared with conventional treatment [7–9]. Favorable effects were also suggested for wet cupping as an adjunct to conventional drug treatment compared with conventional treatment only [10–13]. None of the reviewed trials reported severe adverse events. The number of trials and the total sample size are too small to distinguish between any nonspecific or specific effects, which preclude any firm conclusions. Moreover, the methodological quality was often poor.

The likelihood of inherent bias in the studies was assessed based on the description of randomization, blinding, withdrawals

and allocation concealment. Four of the seven included trials [7–9, 13] had a high risk of bias. Lowquality trials are more likely to overestimate the effect size [14]. Three trials employed allocation concealment [10–12]. Even though blinding patients might be difficult in studies of cupping, specifically wet cupping, assessor blinding can be achieved. One of the RCTs made an attempt to blind assessors. None of the studies used a power calculation, and sample sizes were usually small. In addition, four of the RCTs [7–9, 13] failed to report details about ethical approval.

Details of drop-outs and withdrawals were described in two trials [10, 11] and the other RCTs did not report this information

which can lead to exclusion or attrition bias. Thus the reliability of the evidence presented here is clearly limited. Two types of cupping were compared with conventional treatment including drug therapy. Some suggestive evidence of superiority of dry cupping was found compared with conventional drug therapy in patients with low back pain [8] and cancer pain [7]. However, one study failed to compare the baseline values of the outcome measures [7]. Four RCTs compared wet cupping with control treatments [10–13]. One RCT [10] reported favorable effects of wet cupping on pain reduction after 3 months follow up, without assessing it after the intervention period. However, these positive results are not convincing because no information was given about treatment during the 3 months of intervention. Two further RCTs [11, 12] tested the effects of wet cupping on BPN and showed it to be beneficial in the reduction of pain.

Even though these RCTs showed significant differences at 7 days after a single session treatment, uncertainty about the effectiveness of single session cupping remains due to lack of follow-up measurements. One trial of wet cupping suggested

positive effects of response rate [13], while re-analysis of this results with χ2 test failed to do so (P = .067). Comparing wet cupping plus usual care (or heat pad) with usual care (or heat pad) [10–13] generated favorable effects on at least one outcomemeasure. Due to their design (A + B versus B) these RCTs are unable to demonstrate specific therapeutic effects

[15]. It is conceivable that with such a design (A + B versus B), the experimental treatment seems effective, even if it is,

in fact, a pure placebo: the non-specific effects of A are likely to generate a positive result even in the absence of specific

effects of A.

Reports of adverse events with cupping were scarce and those that were reported were mild. Adverse effects of cupping were reported in one [10] of the reviewed RCTs. Three cases of fainting (vaso-vagal syncope) were reported with wet cupping.

Assuming that cupping was beneficial for the management of pain conditions, its mechanisms of action may be of interest. The postulated modes of actions include the interruption of blood circulation and congestion as well as stopping the inflammatory extravasations (escaping of bodily fluids such as blood) from the tissues [3, 4]. Others have postulated that cupping could affect the autonomic nervous system and help to reduce pain [3, 4]. None of these theories are, however, currently established in a scientific sense.

Our review has a number of important limitations. Although strong efforts weremade to retrieve all RCTs on the subject, we cannot be absolutely certain that we succeeded. Moreover, selective publishing and reporting are othermajor causes for bias, which have to be considered. It is conceivable that several negative RCTs remained unpublished and thus distorted the overall picture [16, 17]. Most of the included RCTs that reported positive results come from China, a country which has been shown to produce no negative results [18]. Further limitations include the paucity and the often suboptimal methodological quality of the primary data. One should note, however, that design features such as placebo or blinding are difficult to incorporate in studies of cupping and that research funds are scarce. These are factors that influence both the quality and the quantity of research. In total, these factors limit the conclusiveness of this systematic review.

In conclusion, the results of our systematic review provide some suggestive evidence for the effectiveness of cupping in the management of pain conditions. However, the total number of RCTs included in the analysis and the methodological quality were too low to draw firm conclusions. Future RCTs seem warranted but must overcome the methodological shortcomings of the existing evidence.

References

[1] J. A. Astin, “Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study,” Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 279, no. 19, pp. 1548–1553, 1998.

[2] S. Fleming, D. P. Rabago, M. P. Mundt, and M. F. Fleming, “CAM therapies among primary care patients using opioid therapy for chronic pain,” BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 7, Article ID 15, 2007.

[3] I. Z. Chirali, Cupping Therapy, Elservier, Philadelphia, Pa, USA, 2007.

[4] S. S. Yoo and F. Tausk, “Cupping: East meets West,” International Journal of Dermatology, vol. 43, no. 9, pp. 664–665, 2004.

[5] Y. D. Kwon and H. J. Cho, “Systematic review of cupping including bloodletting therapy for musculoskeletal diseases in Korea,” Korean Journal of Oriental Physiology & Pathology, vol.21, pp. 789–793, 2007.

[6] P. T. H. Julian and G. A. Douglas, “Assessing risk of bias in included studies,” in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, P. T. H. Julian and S.Green, Eds., pp. 187–241,Wiley-Blackwell,West Sussex, UK, 2008.

[7] Z. F. Huang, H. Z. Li, Z. J. Zhang, Z.Q. Tan, C. Chen, and W. Chen, “Observations on the efficacy of cupping for treating 30 patients with cancer pain,” Shanghai Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, vol. 25, pp. 14–15, 2006.

[8] Y. F. Hong, J. X.Wu, B. Wang,H. Li, and Y. C.He, “The effect of moving cupping therapy on non-specific low back pain,” Chinese Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, vol. 21, pp. 340–343, 2006.

[9] Z. Zhang, “Observation on therapeutic effects of blood-letting puncture with cupping in acute trigeminal neuralgia,” Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 272–274, 1997.

[10] K. Farhadi, D. C. Schwebel, M. Saeb, M. Choubsaz, R. Mohammadi, and A. Ahmadi, “The effectiveness of wet-cupping for nonspecific low back pain in Iran: a randomized controlled trial,” Complementary Therapies in Medicine, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 9–15, 2009.

11] R. L¨udtke, U. Albrecht, R. Stange, and B. Uehleke, “Brachialgia paraesthetica nocturna can be relieved by “wet cupping”-results of a randomised pilot study,” Complementary Therapies in Medicine, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 247–253, 2006.

[12] A. Michalsen, S. Bock, R. Ludtke et al., “Effectiveness of cupping therapy in brachialgia paraestetica nocturna: results of a randomized controlled trial,” Forsch Komplementarmed, vol. 14, p. 19, 2007.

[13] L. Xu and X. J. Yang, “Therapeutic effect of aciclovir combination with callateral-puncturing and cupping in the treatment of 40 cases of herpes zoster,” Tianjin Pharmacy, vol. 16, pp. 23–4, 2004.

[14] A. Moore and H. McQuay, Bandolier’s Little Book of Making Sense of theMedical Evidence, OxfordUniversity Press,Oxford, UK, 2006.

[15] E. Ernst and M. Lee, “A trial design that generates only “positive” results,” Journal of Postgraduate Medicine, vol. 54, no. 3, pp. 214–216, 2008.

[16] M. Egger and G. D. Smith, “Bias in location and selection of studies,” British Medical Journal, vol. 316, no. 7124, pp. 61–66, 1998.

[17] E. Ernst and M. H. Pittler, “Alternative therapy bias,” Nature, vol. 385, no. 6616, p. 480, 1997.

[18] A. Vickers, N. Goyal, R. Harland, and R. Rees, “Do certain countries produce only positive results? A systematic review of controlled trials,” Controlled Clinical Trials, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 159–166, 1998.