By Andreas Brüch, The European Journal of Oriental Medicine

ABSTRACT

SaAm acupuncture is one of the main acupuncture styles of Korean medicine. It encompasses all basic theories of ‘standard’ Chinese medicine. Additionally, it relies heavily on the theory of the Six Qi (liu qi) or Six Climatic Energies. The

Six Qi provide a model of balancing climatic meridian energies that can be used either for directly treating disease syndromes or as a framework for treatment of general constitutional and emotional factors of disease. The purpose of this article is to introduce basic SaAm acupuncture theory, and to highlight its specific features and practical approach by discussing some case examples of the author.

INTRODUCTION

SaAm acupuncture evolved about 300 years ago. Its name is attributed to the assumed founder of the system. The term SaAm (舍岩) is a pseudonym. ‘Sa’ translates to ‘dwell’ and ‘Am’ means ‘rock’ making up a ‘person living in a cave’. According to historical analysis Master SaAm was a Buddhist monk and doctor of Oriental medicine living during the Korean Chosun Dynasty (1392-1910) but there is no further evidence about his true identity or where and when he lived exactly (Kim, 1993). The only remaining manuscript about his original acupuncture concept SaAm’s Essential Rhymes on Acupuncture and Moxibustion (舍岩道 人針灸要訣/SaAam doin chim gu gyeol) was published sometime between 1644 and 1742 (English translation see Lee & Hahn, 2009). Several decades later an individual named Jisan added more extensive comments and case examples to SaAm’s own text, which help to understand SaAm’s primary descriptions of clinical treatments. Over the centuries, handwritten manuscripts about SaAm acupuncture practice by different individuals were handed down and the system was continually developing.

Today, SaAm acupuncture is widely practised among South Korean traditional medicine doctors. However, it is not well known outside of Korea as lectures and formally published instructional material in non-Korean language have only emerged recently. SaAm acupuncture utilises the Shu-Transport Andreas Brüch (Five Element) points of the twelve main meridians in 48 basic combinations of four predetermined acupoints to address both the physical and mental-emotional aspects of illness. General introduction to SaAm acupuncture can be found, for example, in Ahn et al. (2010), Jeon (2016), Kim (1994) or Kim (1998).

SaAm acupuncture theory

SaAm acupuncture utilises all basic concepts found in conventional Chinese medicine acupuncture, like the theories of yin and yang, Five Elements, zang fu syndromes, Six Pathogens and Eight Principles. In contrast to TCM it sets special focus on the theory of the Six Climatic Energies or Six Qi (liu qi) and offers a special framework to understand emotional factors of disease derived from the concept of the Six Qi. The main objective of this article is to explain these specialties.

The Six Qi

The unique aspect of SaAm acupuncture is to combine the concept of the Six Qi with the energetic qualities of the Five Elements. The Six Qi are mainly described in the Huang Di Nejing Suwen chapters 68 to 71. They describe the qualities of

climate and weather of the seasons in nature. The Six Qi are tai yin (Dampness), yang ming (Dryness), shao yin (Heat),

tai yang (Cold), jue yin (Wind/inwards movement) and shao yang (the light of Ministerial Fire/outwards movement). This

climatic understanding is transferred to the human body and the physiological functions of the twelve main meridians.

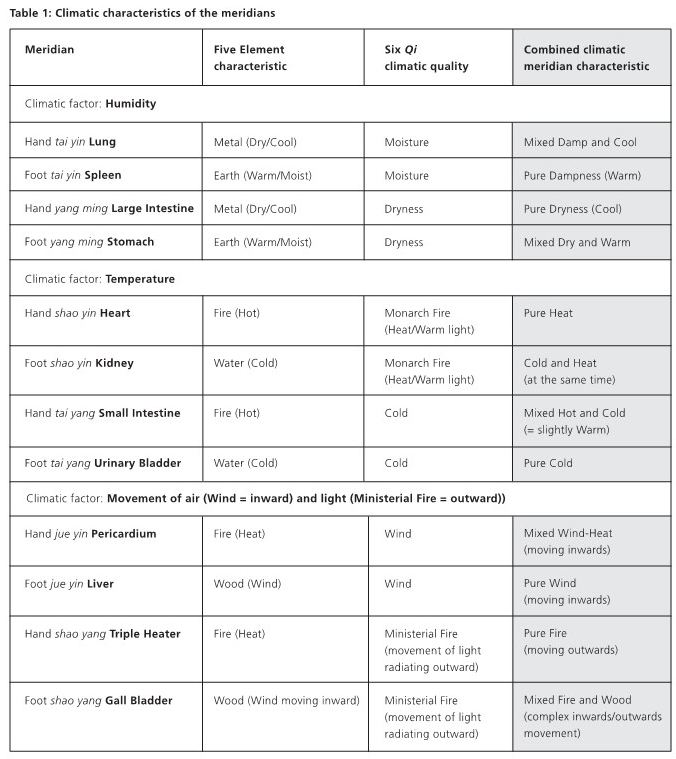

The combination of the climatic aspects of the Five Element theory with the Six Qi creates a unique understanding of the

human body’s microcosm and the individual energetic qualities of the twelve meridians as shown in table 1. Note that in SaAm acupuncture, the meridians’ climatic nature of the Six Qi is considered dominant to the Five Elements. Therefore, in those pairings where the combination of the two concepts appears to be contradicting, the Six Qi decide for the meridian’s main climatic quality. For example, in the Foot yang ming Stomach meridian the Five Element characteristic is Earth/Dampness and the yang ming quality is Dryness, but the overall climatic characteristic has a drying effect.

The combination of Five Elements with the Six Qi divides the twelve meridians into two main groupings. In six meridians

the climatic characteristics of both concepts are identical or congruent, such as the Dampness of Earth and the Dampness

of tai yin in the Spleen meridian. These meridians carry only one pure climatic quality and therefore have a strong effect

on their respective climatic aspect. Six meridians have a mixed or incongruent quality, such as the Heat of the Fire Element and the inward moving Wind of jue yin in the Pericardium meridian. These meridians can influence two climatic aspects simultaneously.

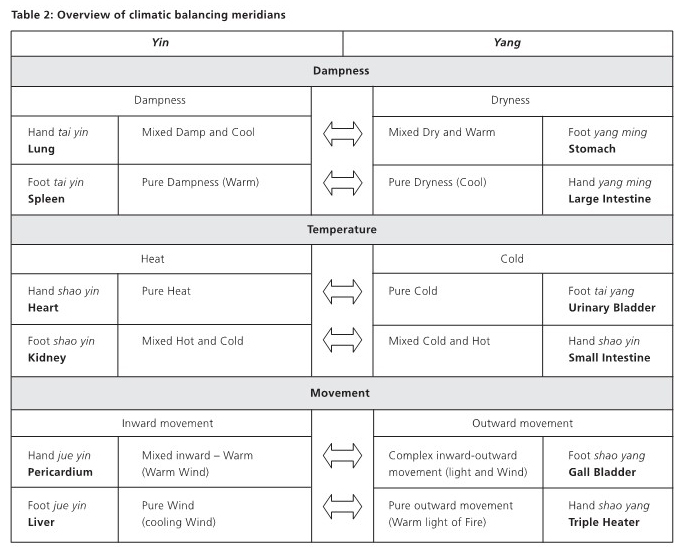

But their influence on the main Six Qi climatic aspect is weaker than in the meridians with pure quality. The twelve main meridians can be grouped into the three main climatic categories of humidity (Damp vs. Dry), temperature (Cold vs. Hot) and (direction of) movement of light and air (inwards vs. outwards movement) (see table 2). The basic strategy of treating health conditions is to harmonise unbalanced internal climatic conditions with the energy of a meridian that has the opposite climatic quality, by tonification of a certain quality that is missing. This can be understood as the classical idea of balancing yin-problems with a yangfactor and vice versa. For example, if we find a very Dry and Cold condition, we can balance this by increasing Moist and Warm aspects. Thus, the tonification of Spleen (Warm and Moist) might be chosen as a treatment. The secondary possibility is to sedate an excess climatic factor directly.

Mental-emotional treatment

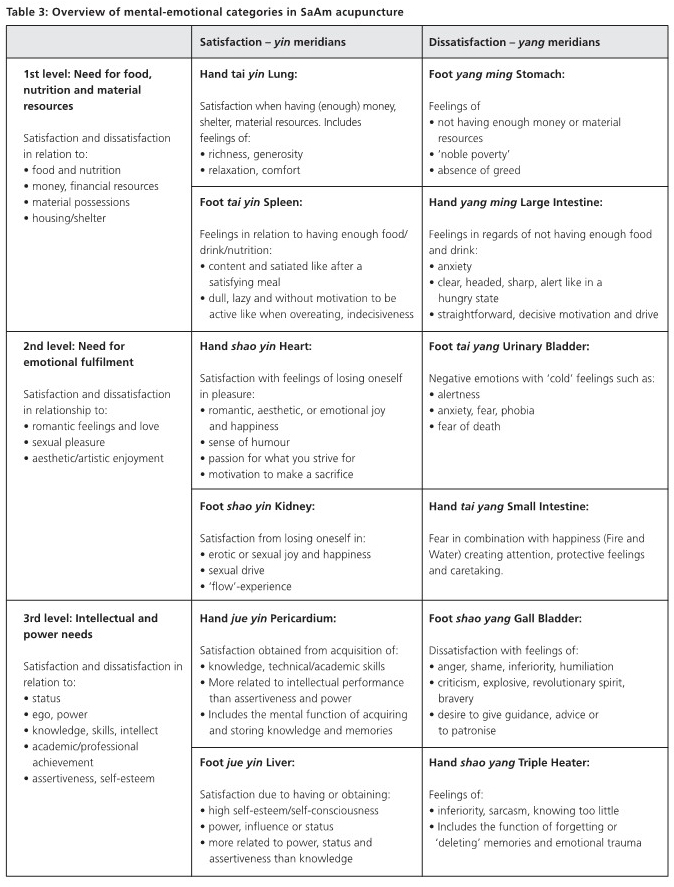

In the 1980s, the concept of meridian energy in SaAm acupuncture was further developed by Hong-Gyeong Kim, a doctor of traditional Korean medicine. He added a model of categories of mental-emotional characteristics found as a distinct feature in each meridian. The treatment principle is identical to physical diseases: Emotional conditions are mostly balanced by increasing the energies of opposite emotional quality or sedating the excess condition directly (Kim, 1991, 1994). Each mental-emotional category is represented by two opposing emotional qualities that balance each other. The classification of these qualities is the same scheme as the climatic categories of the Six Qi. The meridians associated with

these emotional states are responsible for creating specific emotional states. The Yin meridians reflect the satisfaction

or positive feelings of each mental aspect. The yang meridians are associated with dissatisfaction or negative feelings. Thus, the presence of an unhealthy abundance of either satisfaction or dissatisfaction of an emotional quality can be balanced by tonification of the opposing meridian. (Jung, 2019).

See table 3 for descriptions of the mentalemotional categories.

The twelve main meridians can be grouped into the three main climatic categories of humidity (Damp vs. Dry), temperature (Cold vs. Hot) and (direction of) movement of light and air (inwards vs. outwards movement) (see table 2). The basic strategy of treating health conditions is to harmonise unbalanced internal climatic conditions with the energy of a meridian that has the opposite climatic quality, by tonification of a certain quality that is missing. This can be understood

as the classical idea of balancing yin-problems with a yangfactor and vice versa. For example, if we find a very Dry and Cold condition, we can balance this by increasing Moist and Warm aspects. Thus, the tonification of Spleen (Warm and Moist) might be chosen as a treatment. The secondary possibility is to sedate an excess climatic factor directly.

Please note that an excess of positive emotions can also result in unhealthy mental states. For example, the second level is related to the satisfaction of ‘needs for emotional fulfilment’. Compulsion of too much losing oneself in positive pleasure may result in negative consequences. In the extreme, this can end up in thrill-seeking or escapism from the responsibilities of everyday life and can lead to psychopathological syndromes like deviant sexual behaviour or drug addiction. The dissatisfaction side of the mental-emotional dimensions does not mean it is completely negative and undesirable although it contains negative emotions. To a reasonable degree the emotions associated with the yang-meridians have important functions for a healthy mental state because they balance an excess of the positive yin-side and can establish motivational factors in certain situations. For example, the emotions of inferiority, frustration and anger associated with shao yang Gall Bladder can give a person the drive to change an unacceptable or unsatisfying situation. The mental-emotional aspect of SaAm theory has many clinical applications that cannot be discussed in this short text but unfold once the model is understood. For instance, the meaning of the Triple Heater, in contrast to traditional Chinese medicine theory, is to be the ‘mental waste disposal’ of the organism. Specifically, this means Triple Heater energy helps to get rid of mental-emotional ‘waste’. Thus, Triple Heater tonification is applied to drain a person’s mind from traumatic or psychologically negative memories due to post-traumatic stress disease or childhood trauma.

REFERENCES

- Ahn, C.-B., Jang, K.-J., Yun, H.-M. et al. (2010). Sa-Ahm Five Element Acupuncture. Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies, 3(3), 203-13.

- Cha, W.-S., Yoon, D., Kim, J.; Lee, M., Lee, G.-Y. (2014). A study on Sa-Ahm’s thoughts on the four-needle acupuncture technique with the five-element theory. Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies, 7(5), 265-73.

- Choo, T.-C.; Brüch, A., Janowitz, D. (2017). Lehrbuch SaAm-Akupunktur: Koreanische Vier-Nadel-Technik. München: Müller und Steinicke.

- Fruehauf, H. (1999). Chinese medicine in crisis: Science, politics, and the making of “TCM”. Journal of Chinese Medicine, 61, 6-14.

- Gary, M. (2012). Emotions, desires and physiological fire in Chinese Medicine, Part Two: The Minister Fire. Australian Journal of Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine, 7(1), 24-30.

- Jeon, Y.-C. (2016). Daehan minkuk daepyo chimbeob: SaAm chimbeob eui ehae oa hwalyong. Seoul: Saam Books. (전, 용철; 대한민국 대표침법: 사암침법의 이해와 활용. 서울: Saam Books.)

- Jung, Y.-O. (2019). Study on the Sam-Boo acupuncture method. The Journal of SaAm Acupuncture, 1(1), 1-12.

- Kim, D.H. (1993). The literary study on the written date and the background of Sa-Ahm’s 5 element acupuncture method. Journal of Korean Medical Classics, 7, 113-60.

- Kim, D.-H. (1998). Gyogam SaAm doin chimbeob. Pusan: Seogang Printing. (金達鎬, 校勘 舍巖道人 鍼法, 부산: 小康出版社).

- Kim, H.-G. (1991). An Invitation to Eastern Medicine: A delightful journey into an abstruse world. Seoul: Shin Nong Baek Ch’o Publishing.

- Kim, H.-G. (1994). Dong yang euihak hyeok myeong. Seoul: Shinnong Baekcho. (金弘卿, 東洋醫學 革命. 서울: 신농백초).

- Lee, S. (2018). Personal communication with Prof. Sanghoon Lee, Kyung Hee University Hospital, Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Seoul, South Korea.

- Lee, S., Hahn, S.-K. (2009). Saam Five Element acupuncture. Seoul: Jinmundang.

- SaAm doin chim gu gyeol (undated, ca. 1644 – 1742). (舍岩道 人針灸要訣) ‘SaAm’s Essential Rhymes on Acupuncture and Moxibustion’. [SaAm’s original manuscript].